Vladimir Iljitj Uljanov, famously known as Lenin, has always believed cinema to be superior to any other known art form. The prominence of cinema as an artistic medium skyrocketed around the turn of the 20th century, lending credence to Lenin’s belief. While Lenin clearly saw the promise of movies, the Soviet cinema industry struggled considerably following Lenin’s death during Stalin’s dictatorship. However, the Soviet Union’s film industry ushered in a new era following Stalin’s death, spawning many historical features that continue to influence and mold the contemporary film industry.

Filmmakers under Stalin had less leeway than was necessary to express their visions, yet they were nevertheless able to make movies that weren’t merely soulless propaganda. The Soviet industry also gave birth to Andrei Tarkovsky, who later changed our perception of cinema through his timeless masterpieces.

How Statin’s Death Affected Soviet Cinema

After Stalin’s death in 1953, his replacement, Nikita Khrushchev, gave a private lecture in 1956 in which he castigated Stalin’s part in suppressing creative control in the various arts and replacing it with ordinary, emotionless, and bland agitprop designed to establish a “cult of personality” around Stalin. Throughout Stalin’s rule, discussions concerning World War II were rare, and when they happened, they seldom reflected the true atrocities and hardships endured by troops and civilians. It took a few decades for Soviet directors to adjust to the newfound freedom brought on by Stalin’s replacement, but once they adjusted, they began producing films that dared to address topics that had previously been taboo. One such picture is The Cranes are Flying (1957), which depicts a lady’s yearning for her sweetheart during World War II after he is inducted into the Soviet Forces. It marked a departure from stifling censorship in Soviet cinema and introduced novel themes and subjects.

The Soviet School of Cinema has its own unique attributes, such as its preference for a particular subject or its own approach to editing, much like any other national filmmaking tradition. Sometime in the 1960s, directors began producing WWII movies that were overtly critical of the Soviet Union but yet had aesthetic elements and avoided becoming cruel propaganda, depicting the losses suffered by the forces and civilians from a more nuanced perspective. There were numerous films inspired by historic events, such as Sergei Bondarchuk’s War and Peace from 1966, which was adapted from the novel by Leo Tolstoy of the same name. This seven-hour film received an Academy Award for best foreign picture despite having an overall budget of one hundred thousand dollars. This proved to the world at large that the Soviet Union was a bonafide cinematic powerhouse.

Andrei Tarkovsky And His Timeless Masterpieces

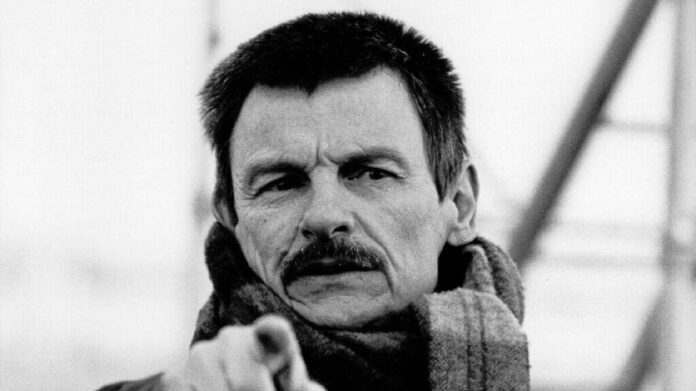

Geniuses like Andrei Tarkovsky certainly need no introduction who played a major role in revolutionizing Soviet Cinema. Andrei was born on April 4th, 1932, and left the world on December 29th, 1986, the very same year his film “The Sacrifice” was shot. Andrei was forced to shoot his film in Sweden since the filmmaker was barred from the Soviet Union. Though he could only direct seven full-length features, Tarkovsky is widely regarded as the aesthetic and creative vanguard of Soviet cinema. His tales generally deal with psychological or philosophical themes, and Stalker is a prime exemplar of this characteristic. His pictures frequently featured the recitation of poems, an artistic medium that has grown to be identified with Russia and the Soviet Union. Tarkovsky’s father, Arseniy Tarkovsky, was a famous poet; thus, it’s possible that he got his taste for poetry from him.

His films are famous for their prolonged shots of natural settings, particularly muddy potholes, lakes, and ravines. His films are relatively quiet, aside from natural noises like wind or water that he preferred to separate and combine because he believed a particular sound might correspond with the feeling that the visual aimed to generate. Rather than emphasizing what we, the viewer, should perceive from a sequence, he frequently picked the components which will be stressed in a scenario based on how the characters depicted in the movie are experiencing it. Ultimately, Andrei relied on the protagonists to convey his feelings to the viewers. It doesn’t matter if it’s the creatures in “Stalker” or the watery world of Solaris; nature frequently played an important role in Tarkovsky’s works, contributing to the themes, aesthetics, and narratives in question. The landscapes and environments shown in his films often have a Soviet twist. He also thought that adding a new element to the picture, like mist or ash, would make the scenario more realistic and draw the spectator in.

The Propaganda And Creative Restrictions

Soviet cinema had a lengthy and storied history of propagandizing against the Soviet regime and celebrating its achievements, but that didn’t stop filmmakers from wanting more liberty to express themselves. Andrei was, for some time, able to avoid controversy by making his work more personalized and making it difficult for anybody to say it was anti-Soviet by hiding the content of the picture underneath philosophical and mystical concepts and exploring issues in this manner.

It’s not true that every Soviet-era movie is terrible or poorly made because of imposed restrictions. Rather, the creator had to find ways to function around the limitation, leading to creations that would have been unachievable under normal circumstances. Several of the Soviet Union’s best flicks are pro-Soviet in nature, such as Come and See or Battleship Potemkin, which were made in the 1930s. Great works of art like Come and See War and Peace and any picture by Andrei Tarkovsky would’ve never existed without the ideas and perspectives that the Soviets fostered.

It wasn’t until the later part of 1991 that the Soviet Union ultimately disintegrated, following a period of constant instability. Naturally, a lot had transpired during this period, as several regions had campaigned for freedom. It’s true that movies have always been primarily motivated for money making, but in those years, this trend intensified, making mainstream filmmaking somewhat like Hollywood.

There’s no doubt that artistic freedom is necessary, but the absence of it can create wonders. Take the case of Tarkovsky; when an artist is given limited opportunities or is under constant scrutiny to effectively communicate his notions, the resulting work is often superior. Perhaps the most important lesson to be learned from Soviet cinema is that the liberty to express oneself creatively doesn’t always result in a masterpiece but rather that the circumstances in which we make them are among the most important factors in our work.