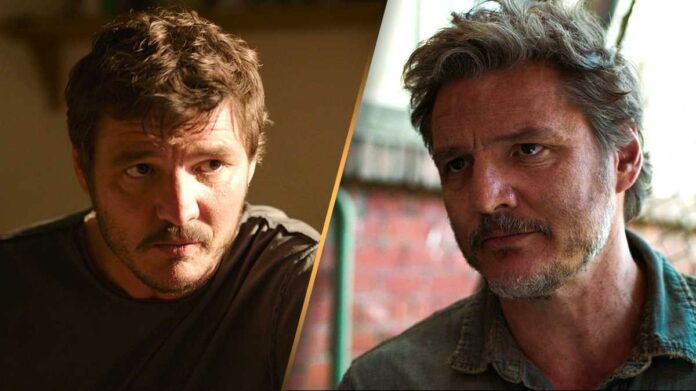

Whenever a new HBO show is announced, fans of TV can almost foresee the delight that is about to tag along with its signature gray characters. There’s a certain morally ambivalent intrigue that invariably surrounds the characters HBO shows deem worthy of exploring. And there’s hardly anything as seductive as a questionable protagonist you have to keep making excuses for. You are to observe them closely, justify their lack of self-awareness, and inevitably root for them, as somehow, and by design, they’re the closest thing to a hero that you will come across in the emotionally hefty narratives. It may be too soon to tell if the TV adaptation of the crowd-favorite game “The Last of Us” has done justice to its revered main character, Joel. But the pilot’s faithful approach toward establishing all the “whys” to all that Joel is does promise a story that won’t lose sight of its primary goal—giving the fans of the game and the fans of TV a complex protagonist to celebrate. And let’s all admit that no one else can treat Joel with the extraordinary authenticity that Pedro Pascal can bring to the character.

Joel was haunted even before Cordyceps massacred the world. A war veteran who evidently brought back emotional scars from Operation Desert Storm didn’t particularly seek help for the same. All we know is that Sarah’s mother is not in the picture. We can assume that it couldn’t have been easy for someone like Joel to raise a daughter by himself. From what we see of Sarah, she hasn’t really had the privilege of a breezy life either. The weight of taking care of her father shouldn’t rest on Sarah’s young shoulders, but that is how it is in the Miller household. It’s not that Joel doesn’t love Sarah, but the discernible discontentment of a single parent has a way of infiltrating a child’s psyche. All Joel can afford to concern himself with is making a living with his construction job. The pessimism and selfishness he has gained along his life, which hasn’t particularly been easy, have made him too self-absorbed to be okay with dividing up the profits, even with his own brother Tommy.

Perhaps it is his traumatizing experience of the war that has turned Joel into a person who is incapable of caring about anyone other than the people he is closest to. The usual military sentiment of being protective of all people isn’t necessarily what Joel associates himself with. It is staggering how nonchalant he is about not helping a family in the dire situation of the pre-apocalypse riot in Texas. “Someone else will help them” is what Joel justifies his selfishness with, and he doesn’t even feel the urge to look back. While it is all meant for the protection of Sarah, that is the very thing he fails to accomplish when she is shot and killed by the military. The useful aspects of his combat experience don’t kick in when they’re needed, and holding her in his arms in front of the enemy is something Joel will never forgive himself for. He doesn’t just lose the only person on earth that he loves abundantly; Sarah’s death also weighs heavily on the mind of the father, who blames himself for not having the prompt instincts that could have saved her life.

Joel never really recovers from the trauma of having his daughter die in his arms. What died along with her was the last remaining softness in his heart. When we see him throwing the unconscious little kid into the QZ fire pit, we see a man who has turned to stone. Life stopped for him the moment Sarah died, as did time. The watch that most likely broke during the chaos of the open fire that killed her still remains on his wrist as a constant, haunting reminder of the tragedy. Sure, he has found some warmth in his relationship with Tess. But Tess being as severe as he is, makes it easy for him to share the kind of tenderness that doesn’t need an affectionate expression.

Pedro Pascal embraces all that is wrong with Joel and gives us an idiosyncratic picture of a man whose only mode of survival is extreme pragmatism. Neither does the man possess an ounce of loyalty towards FEDRA’s austerity, nor does he associate himself with the radical Fireflies. He hardly even wishes to sit on the fence and only does what he needs to do to get what he wants. While he does put up a convincingly impenetrable front, on the inside, Joel is falling apart. Chugging down some sleeping pills with booze is how he puts himself to sleep. His cynicism toward any cause, however meaningful it may be, has caused a rift between him and his brother Tommy. Words of hope irk him to the point of wanting to beat someone up for uttering the Fireflies slogan of “following the light.”

Joel isn’t incapable of caring about others. Nonetheless, he deliberately avoids attachments as a PTSD response. The fragility that he hides inside his shell of strength is what he desperately wants to protect. Joel is more terrified of the feeling of loss than he is of the more immediate threats. 2023 Joel is a person who isn’t apprehensive about holding a gun to a child’s face. The kind of aggression that it takes to be able to threaten a child with physical harm isn’t something that just happens to a person who didn’t always have darkness in his heart. The trauma that he went through only made room for the lurking darkness to become a part of his extrinsic personality as well. The most axiomatic expression of Joel’s PTSD finds an outlet when he is faced with a parallel situation that takes him back to the circumstances of his daughter’s death. It isn’t his protective instinct that makes him save Ellie. Killing the FEDRA man becomes an arbitrary way for Joel to unleash the rage that has been consuming him from within for 20 years. At that moment, the man we see is the ghost of 36-year-old Joel, trying furiously to go back in time and change the traumatic course of events.

See more: ‘The Last Of Us’ Episode 1: All Easter Eggs And Hidden Details, Explained