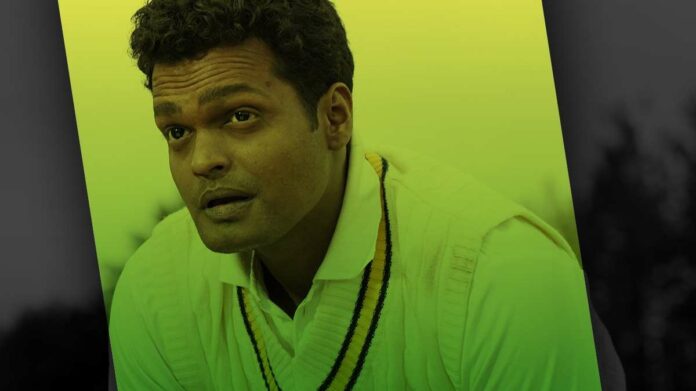

For me, biopics have become quite a dubious cinematic genre. On the one hand, we might get a great movie about a famous personality, but on the other hand, the movie could be so formulaic that it’s hard to appreciate. The 2023 movie about the Sri Lankan off-spin bowler Muttiah Muralitharan, titled 800, falls into the category of a well-made biopic with a great lead cast, but eventually, the beats of the movie are placed at such intervals in the film that it becomes too predictable at times. The film very nicely depicts the prodigy’s early years, showing us the historical background in which he was brought up. The latter half, when Murali was world-famous, is weak, as it offers very little insight into the man. The major events of his cricketing career are rushed and ticked off one by one; the problem is that they are dealt with very superficially. The performances are good, but the writing borders on being melodramatic. 800 risks being a run-of-the-mill biopic; perhaps what saves it is the endearing personality on whom the movie is based and how he became the beacon of hope for Sri Lanka.

Spoilers Ahead

Plot Synopsis: What happens in the Film?

The movie’s title refers to the 800 test wickets that Murali bagged during his career. He completed the feat in a match against India. The movie begins while the last match of Murali’s test career was still ongoing, and he was still 7 wickets short of the unbelievable mark of 800 test wickets. A naysayer reporter went to a senior journalist, Mugunthan, who was said to have great details about Murali’s career. The editor wanted a comprehensive article ready for Murali’s retirement and in case he took the 800 wickets. Mugunthan had a whole encyclopedia, tracing Murali’s career from the very beginning. The young reporter was quite unmoved by Murali’s performance, and he didn’t care if he achieved the milestone, but Mugunthan had a message for him. He wanted to prove why Murali mattered and what his achievements stood for. He began telling him that Murali’s parents were Tamilians who had come to Ceylon during the British period, and how Murali had grown up in the seventies during a period of great tension between the Sinhalese and Tamil populations in Sri Lanka. What kept Murali occupied and away from radicalization was his love for cricket. Murali’s grandmother’s blessings worked wonders, and Murali kept overcoming initial obstacles and got very close to playing international cricket before he even reached his twenties.

How did Murali get into the national team?

The talent was always there. Ever since a young age, he was noticed by his coaches, and a bright career lay ahead of him. But the problem was that he had little support from his father, who thought that there would be issues as he was a Tamilian and was seen as an outsider. The country was still not completely over the wars that began from 1977, where his family lost a lot of business and were almost killed during the pogroms. But Murali’s resolve ensured that he kept honing his skills, and after a few hiccups, he got to go to England to perhaps play in his debut match. Arjun Ranatunga, Sri Lankan cricket’s superstar and captain of the national team, had noticed him bowling in a local match and was quite impressed by his talent and unusual bowling action. That didn’t immediately get him into the playing eleven, but the aim was achievable. His trip to England was disappointing, as he wasn’t picked to play a match, even though he had taken over 100 wickets in local matches. Dejected, Murali almost joined the family business, but his passion didn’t allow him to. He started practicing at Colombo Cricket Club, and in 1992, Australia came to play Sri Lanka, and it became a turning point in Murali’s career. Murali bowled brilliantly in the practice match, and later, when Australian spinner Shane Warne performed outstandingly well in the first test match, Ranatunga decided to get Murali into the team for the second test match. Murali’s dream had come true, and he didn’t disappoint. He performed brilliantly, winning match after match for Sri Lanka, on his way to rival Warne as being the best spinner of all time.

Why was Murali accused of ‘chucking’?

Murali’s family had little to no knowledge of cricket, and it was endearing to see them support their son nonetheless. Murali was in a spot of bother when the Australian umpire called him out for ‘chucking’, which meant he was bending his elbow more than the allowed limit, making his bowling action illegal. Murali’s arm had a natural bent, which gave the appearance that he was bending his elbow to spin the ball much more than it normally would. Ranatunga stood by his side, but it had become an international matter. Were all those wickets he took now under scrutiny? Indeed. More than that, his family had their own theories. They were still worried that Murali was being targeted because he was a Tamil. Murali never doubted the Sri Lankan cricket board, but constantly worrying about his ethnic background was soon going to take its toll. The only way for Murali to prove that he wasn’t ‘chucking’ was to undergo a test with the professionals, and after the test, they were positive that he wasn’t. Murali was almost out of the World Cup, but the board didn’t leave his side and chose to select him in the squad, even though there was a huge chance that the umpires would call him out for chucking. In 1996, Sri Lanka went on to win the One Day International World Cup despite the country’s extremely ugly situation and terror attacks becoming commonplace.

How was Murali cleared by the ICC?

Despite the challenges, Murali went on to become a feared bowler in both Test and One-Day cricket, amassing a huge number of wickets. He proved himself in foreign lands as well, performing brilliantly against top-quality teams such as England, Australia, and India. But there was always this allegation hovering over him that all his achievements were a result of illegal bowling. There was a media rivalry between Shane Warne and Murali that had been taken in a very unhealthy manner. People wanted an ugly spat between the two. Shane mentioned once, in jest, that Murali took wickets against the minnows while he was the true champion of spin bowling. Murali didn’t mind these comments, but there was still a feeling of wanting to prove to the world that his action was legitimate.

Murali put his career on the line when he planned to undergo a video-recorded test wearing a splint over his elbow. He wanted to prove to the officials and to the world that he didn’t bend his elbow. Wearing the specially made splint, which covered more than half of his bowling arm, could injure his shoulder, and at that age, it could well become a reason for him to retire. Yet Murali undertook that endeavor in hopes of clearing his name. His shoulder was a little damaged, but at last, he was cleared by the International Council of Cricket (ICC), the highest governing body of cricket. Their word was law, and yet there were some, like the young reporter, who saw him as a ‘chucker’. Where were all these feelings coming from? There was surely prejudice involved, as Murali was Tamilian. Even when he decided to marry Madhi, an Indian, he had his wedding in Chennai, capital of Tamil Nadu.

People in Sri Lanka were divided on how to view Murali. He had done so much to unite the country. He had become the UN Ambassador and went to see Prabhakaran, the leader of the LTTE (a rebel group), trying to bring peace between the Tamil rebels and the Sri Lankan people. He had almost been killed in a terror attack in Pakistan, and some people were so blinded by hate and prejudice that they wished him harm. Muthungan tried to instill a sense of belonging in the young reporter, telling him that Murali wasn’t just a cricketer but a beacon of hope for a better, more united Sri Lanka. If the young reporter had lost his parents in the Tamil-Sinhalese conflict, so had Muthungan’s son lost his legs, in one of the ‘96 blasts. He was a talented bowler himself, but now he could only walk with a crutch. The loss didn’t mean that Murali could become the focus for people to project their hate on. Now that he had been cleared by the ICC itself, it was time to respect the national cricketing gem. Murali finished with 800 wickets in test matches, picking up the 800th against India and winning the match. He is still the highest wicket-taker in international cricket, with over 1000 wickets under his name, a record that some say will never be broken.