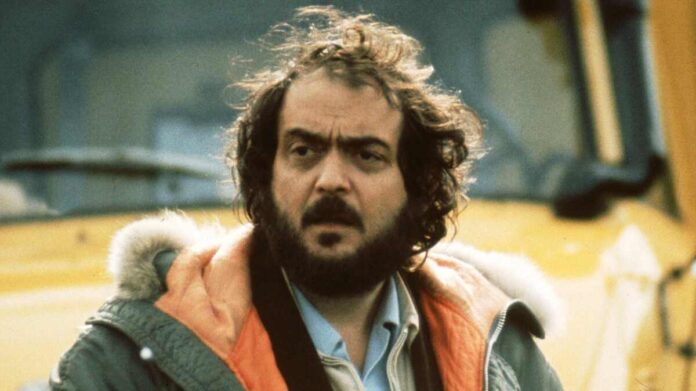

Following his untimely death on March 7th, 1999, the legendary filmmaker Stanley Kubrick has continued to be revered as a pioneering visionary by audiences of all ages. Oddly, the guy who had envisioned a stunning future decades ago didn’t live long to witness the massive technological advancements that contributed to people debating his movies on the internet, but that’s precisely what happened after his passing. His films often appear on streaming platforms, and his passionate fandom discusses them in online communities.

Kubrick’s popularity stems from several sources, but what stands out mainly is his unique approach to filmmaking. It’s safe to say that Kubrick’s films were unlike anything else coming out of Tinseltown. His movies had a distinct visual style because of the meticulous planning that went into each shot. Compared to other films of its time, Kubrick’s works stand apart. He wasn’t looking to capture the typical dramatic moments in movies. Instead, the genius was on the hunt for some deep intuitive experience that would shed light on some core truth about the human psyche.

Kubrick’s rise to fame was unexpected, to a certain extent. He had dropped out of college before graduation, and his main hobbies in life were clicking pictures and beating his friends at the game of chess. The filmmaker spent around half a decade at Look, and his knowledge and expertise had led him to direct his own movie. His debut picture follows the life of a fighter as he prepares for a match. It is less fiction and more of a documentary.

The picture did exceptionally well at the box office, and Kubrick was fortunate to build connections that proved to be helpful in the future. In 1952, he began working on what would be his debut feature. Kubrick oversaw much of the movie’s technical elements alone since the production cost could only cover staff of 15. The outcome did not satisfy him at all. He discussed his feelings at the time and how the production budget had influenced him in interviews. The picture wasn’t very successful, but it aroused enough curiosity to offer Kubrick a second shot, which he made the most of for the remainder of his filmmaking years.

Kubrick’s Way of Integrating Silence and Melody Into His Movies

A film’s opening is a critical element of the whole production. It should establish the story’s mood and give the audience a reason to care about what happens next. The objective of the opening is to put the audience into a trance of intense focus for the remaining duration of the movie. Kubrick was as aware of this as any other director. However, he brought his unique approach to the concept.

From “Clockwork Orange” to “Shining” to “Full Metal Jacket,” all of Kubrick’s films have two standard opening devices: silence and melody. The opening scenes of every film, save for “Barry Lyndon,” begins with music but no usage of dialogues. This music, when coupled with a quiet visual, perfectly establishes the tone and mood of the film. It evokes an emotional response from the audience. Just as the mood of each of his movies shifts from subject and technique, so do the emotions conveyed by each of his individual shots. Every one of them is perfect because it manages to sum up the spirit of their respective films. In “Dr. Strangelove,” Kubrick’s most notable work, the opening titles roll, and we see an American B-52 getting refueled while “Try a Little Tenderness” soothes the background. It’s a gentle tune that’s easy on the heart and sums up the comedy of what is about to happen next.

Many people think his next movie, “2001: A Space Odyssey,” is his best work ever. In the annals of cinema, it stands majestically for its classic opening sequence. There is a two-minute blackout at the film’s start, during which the music “Overture: Atmosphere” takes center stage. Next, the moon gradually emerges from the fading sky. As the camera rises, we see that the moon, Earth, and sun are correctly aligned. Kubrick hoped that his film would convey some of the awe and mystery of interstellar space to the audience, and it did. His following two pictures also employ unorthodox usage of stillness which ultimately works to the benefit of the story.

Kubrick Always Chose The Road Less Traveled By

As a filmmaker, Stanley Kubrick was interested in how people’s morals would hold up when confronted with misfortune and tragedy. He used fiction to show how this conflict might play out. Instead of following the standard technique of tailoring the plot to the protagonist, Kubrick often invented or reworked a personality in order to pursue a story that was outside of the protagonist’s purview. The movies “A Clockwork Orange” and “Dr. Strangelove” are prime examples of Kubrick’s approach to creating this image. Both works depict a society in disarray and ruin, but they do it in their own unique way. The people living in this universe are utterly oblivious to their immoral and ludicrous actions.

Kubrick understood that the best means to show the idiocy and stupidity of human behavior was through absurdity. In the film “Dr. Strangelove,” humanity ends when a crazed commander orders a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union because he is confident that the country has poisoned his supply of potable water. The Russians retaliate, but the crazed commander isn’t aware that the “Doomsday Machine” would fire nuclear missiles at each and every part of the world until it was destroyed. The good guys attempt to deal with the crisis by ordering a nuclear strike on the commander’s barracks; they are successful in doing so, but only after one of the warplanes breaks contact and misses the transmission, causing the explosion.

Peter Sellers’ roles are supposed to symbolize how people react when faced with administrative ineptitude. The movie’s most iconic quote, “Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here; this is the war room!” reveals President Muffley to be a bumbling clown who strives to seem strong and in charge but has no clue whatsoever! Dr. Strangelove is just as insane as the mad commander and appears to eagerly anticipate the impending devastation. Captain Mandrake, who tries all in his ability to avert disaster by decoding the fail-safe password, is the movie’s only bright spot. In spite of his accomplishment in deciphering the encryption, his efforts ultimately prove fruitless since only one of the planes can really intercept the transmission.

The theme of the world’s destruction in “A Clockwork Orange” is eliminated in order to focus on how immorality is reshaped to serve the interests of the state. By introducing Alex DeLarge, a juvenile miscreant who commits severe crimes and depravity, the movie explores significant issues like free will and hypocrisy. After his imprisonment, Alex is subjected to the Ludovico Experiment, a therapy designed to eradicate aggressive tendencies. After enduring the torturous rehabilitation, during which he was made to repeatedly see graphic depictions of bloodshed and destruction, Alex no longer had any desire to resort to physical violence. Therefore, the authorities viewed the therapy as effective and promptly released Alex.

Once back in the community, Alex is met with nothing but disdain and hostility from those who knew of his criminal background. Alex tried to commit suicide by leaping out of a second-story window after being tormented by the guy he had attacked. He makes it through the attempt unscathed and, as a result, is held up as a shining example of the state’s efforts to reform juvenile offenders. Alex imagines an obscene picture and says sarcastically, “I was healed, okay.” This is the last line of the film. The movie’s climax leaves a lot to the imagination. The end product is visual and grotesque without necessarily being aggressive. It may be a sign that Alex has become a servant of the state, which condones bad behavior when it is perpetrated to serve those with money and power.

Kubrick’s Rorschach Approach

Kubrick wanted the audience to feel strenuous joy and fulfillment while watching most of his films. Like a Rorschach experiment, he approached cinema by trying to create a plot in which the audience is left to draw their own conclusions about the relevance of various events and props. His films’ prologues provide a window into his motivations. All of his films explore the conflicting nature of human behavior. He tries to show that the tension between doing “what is good and what is evil” arises from the fact that our institutions serve different interests. But he is fully aware that we, the people who make these institutions possible, are also participating in their promotion. To summarize, the central theme of every picture he makes is the paradoxical way in which our need for order becomes the ultimate ingredient for anarchy.

Just these couple of examples from his projects demonstrate why he is often viewed as one of the greatest filmmakers and storytellers who ever lived. His works are intricately structured and fascinating because of the themes and subjects they explore. He was a genius—a true visionary who grasped the immense potential of the visual medium.