American filmmaking has always been blessed with great filmmakers who swore to construct a better future for the art form. In the beginning, Americans thought of the film as an illegitimate version of the theater; D.W. Griffith helped them understand that film was a unique art form. He also improved many filmmaking devices that helped legendary directors like Raoul Walsh create a new storytelling format in “High Sierra” (1941). Some pioneers always set the stage for the later directors, and brilliant talents carried the chain; thus, Hollywood became the most successful in every aspect of filmmaking.

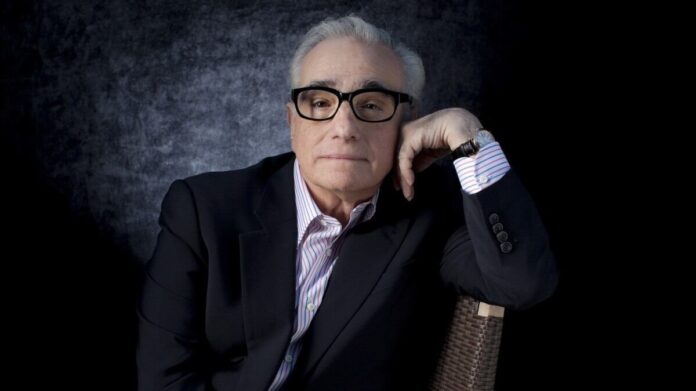

Today, we are about to close our discussion on Martin Scorsese’s journey through American movies by highlighting some of the iconoclasts and their brilliance in the field. How far have we come? We understood the genres, the importance of storytelling, the silent era, the age of sound, three-strip color, unorthodox camera movements, and even special effects that gradually changed the course of American movies. Of course, it was never only technology but the collective brilliance of the makers and actors that always kept the art form on the right track. We have enlightened ourselves with the filmmaking style of many master directors like D.W. Griffith, Raoul Walsh, Erich Von Stroheim, Jacques Tourner, Frank Capra, and Billy Wilder. Today’s discussion will solely focus on some of the directors who immortalized iconoclastic films.

How Did Charlie Chaplin Directly Question Fascism Through His Film?

In his first ever talking picture, “The Great Dictator” (1940), screen legend Charlie Chaplin aimed at the fascist powers. He was so direct in his approach that it had an immediate impact on the world. Martin Scorsese described Chaplin’s work by saying, “At the risk of infuriating America’s isolationist forces, Chaplin took on the dictator single-handedly.” Presenting a comedy about topical horrors such as racial persecution and concentration camps was not the only challenge Chaplin had to overcome; he even went further with his approach. Apart from being the monstrous dictator Hynkel, Chaplin also played himself as the character of a victim who was a Jewish barber. However, rebels like Chaplin himself had to get around the censors as the contents of American films were still strictly controlled. They suppressed adult themes and images too often. But, as long as we are talking about iconoclasts, nothing usually stops them from showing whatever they want.

In The Age Of Rebels, There Was “A Streetcar Named Desire”

After World War II, the audience’s taste rapidly changed as they wanted to see pictures that dealt more with realism than fiction. Several filmmakers broke Hollywood’s rules, with Elia Kazan leading the charge. In his “A Streetcar Named Desire” (1951), Elia Kazan caused the first significant breach in Hollywood’s Production Code. While adapting the story to the screen, he went against every possible barrier to keep the integrity of Tennessee Williams’s drama. For this, he had to establish the tremendous lustful desire of Stanley and his pregnant wife, Stella. Martin Scorsese showed some close shots of Kim Hunter, which were never released. The studio decided to cut them and replace the original jazz score with traditional music. Kazan was trying to introduce a new acting style. According to Scorsese, the reason was that “the Legion of Decency objected to their sensuality.” Kazan said, “I have revealed things that actors didn’t know they were revealing about themselves.” According to Kazan, Marlon Brando was the only capable actor who “had the ambivalence,” which was essential to establishing humanity in terms of strength and sensibility.

Billy Wilder’s Comedies And Their Contribution To American Filmmaking

Billy Wilder’s comedies were just as iconoclastic as his dramas, as his brilliance outsmarted his genius over time. According to Martin Scorsese, his 1961 classic “One, Two, Three” was the most iconoclastic film in the “Kennedy years.” Scorsese described the film as “a savage political farce that dared ridicule all ideologies at the height of the Cold War.” Billy Wilder preferred to see good taste as another format for censorship. If he was accused of being vulgar, that meant to him he was closer to life. “One, Two, Three” was a massive success in Germany after 25 years of its release. The movie showed the wall where nobody could get through East Berlin and West Berlin. After 25 years, the wall was almost gone, and people started laughing at the callousness of the Russians and the ideocracy of the Americans. After many years, the film remained remarkable, and an iconoclast had won.

Arthur Penn, Stanley Kubrick, And John Cassavetes: Last Of The Mohicans

The rulebreakers already set the tone for the new directors to explore different ways. The revolt had already started long ago, and now came the three masters who announced the victory against the Legion of Decency. By the end of the 1960s, all the production codes were almost broken. Arthur Penn’s “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967) put the final nail in the coffin. The hypocritical old studio system feared being accused of showing the glory of the outlaws growing among the youth. They had these stupid rules like you couldn’t fire a gun in the same frame as somebody getting hit. There needed to be a film cut in between the shots. Arthur Penn said, “We should show what it looks like when somebody gets shot,” and just like that, another chapter of the old rulebook was broken.

When the production code did not survive in the late 60s, sexuality and the complexity of the human psyche were the remaining frontiers. It was now up to Stanley Kubrick to be playful with his unique ideas and approaches. He came from independent production and film noir to create his imaginative world in cinema. Kubrick left the studio projects and moved to London before shooting his 1962 masterpiece “Lolita.”He stopped making films in Hollywood ever since and became one of the rarest iconoclasts who enjoyed the luxury of operating entirely on his own. In “Lolita,” he established a middle-aged man infatuated with a “sexually precious minor” named Lolita. Showing something like that was taboo, but Kubrick proceeded even further. He showed the complexities of the human psyche by showing the man’s obsession with the minor and ended up in a mental hospital.

John Cassavetes created a style where he always kept the emotions of his characters upfront. His approach was primarily focused on people and how they reacted to the little details that were taking place around them. Love always carried the laughter and games, the tears and the guilt; essentially, it was an emotional roller coaster, and Cassavetes built his brilliance around it. In his 1968 classic “Faces,” he introduced a middle-class housewife living in agony over her failed marriage. A younger man loved her, and they were at her place for the night. The following day, he found her unconscious, and that startled him. Cassavetes introduced the style where his films were made on a credit plan. His protagonist was setting up one psychodrama after another. According to Scorsese, “Cassavetes embodied the emergence of a new school of guerilla filmmaking in New York.” In an interview, Cassavetes said, “I think what everybody needs is a way to say,” Where and how can I love, be in love so that I can live with some degree of peace?” He continued, “I have a one-track mind. All I’m interested in is love. “

Conclusion

Filmmakers brought down the production codes; there was freedom for the filmmakers. Iconoclasts have won the war. American filmmaking had a lot of ground to cover. Everything seemed fair, but this never happened within a few years. It took many decades to turn down every order, the studio system, and the policies of the executives. Some filmmakers kept on fighting and became indestructible, such as D.W. Griffith, Raoul Walsh, Orson Welles, Jacques Tourner, Charlie Chaplin, Stanley Kubrick, Alfred Hitchcock, etc. Some decided to stay put, some even punched executives, and it cost them badly. In wars, most die hopeless, and some are remembered, but a new territory is always marked. From the time of the storytellers to the time of the smugglers, iconoclasts carved out new territory in American filmmaking: creative freedom before all else. Modern-age filmmakers like yourself are privileged to know a rich history of such battles and how films have won through time.