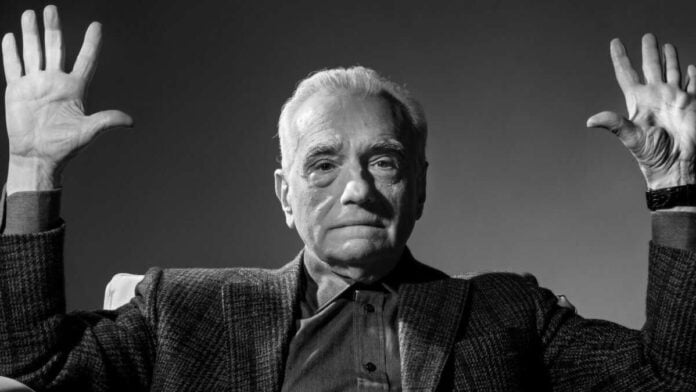

We have understood the patterns of American filmmaking, their transformation, and how they tackled one obstacle after another. We have also learned how the American film industry eagerly embraces the advancement in filmmaking techniques, no matter what the challenges were. This brings us to today’s discussion, i.e., how technology has become a tragic transition for some silent film directors. Martin Scorsese said that even the most minor aspects of filmmaking started to change, like how a script conference required new skills when sound came along, and that change demanded more receptive directors and technicians.

Legendary director King Vidor once described this transition in the simplest of words. He said the American filmmakers were so involved in a pantomime that they were somehow living in it. When someone would come and tell a story to the rest of the crew members, he would do the whole thing in the format of a pantomime. The entire process was distorted when suddenly the era of sound hit. He continued by saying they had to think about something they had never cared about before: “the dialogues.” Vidor explained that he had always thought entirely in images and actor’s movements his whole life, but now he had to figure out the words too.

The Struggles At The Beginning Hollywood Faced Using The Sound

Anything new takes time to understand. It would be best to master them first, then make them a part of your style. If you don’t have the slightest idea about the new camera or grip that you are going to use for your shoot, and then just randomly show up on set, then you are bound to struggle to use it. American filmmakers also faced many difficulties while using Sound as a device in their films. They first started with sound experts who had almost no idea about filmmaking. In the beginning, they placed the cameras in a soundproof booth; William Wellman once mocked this technique by saying that creaking floors started receiving more attention than creaking stories. This method had many drawbacks, such as the actors having to be kept within the range of microphones.

Just when most people thought the movies had stopped moving with the introduction of Sound, some American filmmakers were so stubborn that they refused to be shackled by any means. When they started understanding the technicalities, they began improvising with its help. For example, they used the microphone as a lantern in a shot in “Anna Christie” (1930). The actors could not move far from the microphones, so they placed the microphone right in the middle of the shot, using it as a prop.

The Evolution Of American Filmmaking By Using Sound To Intensify Drama

Directors like Rouben Mamoulian, Frank Capra, William Wellman, and Tay Garnett helped American filmmaking by getting the camera moving again. They featured some of the most fluid camera moves and also introduced very long takes. We have previously talked about how directors started transforming themselves as illusionists by using technology as a tool in filmmaking. Using Sound as a device encouraged the illusionists to enhance reality. For example, George Hill’s 1930 classic “The Big House” helped the audience understand reality only through sound effects. The continuous footsteps of the convicts suggest that they all are anonymous robots, but as soon as you hear their voices, they come alive. Also, in “Scarface,” Howard Hawks demonstrated how Sound and visual effects could blend precisely. He mixed the Sound of bowling with the gunshot and established a perfect metaphor. William Wellman introduced the whole climax without showing anything in his “The Public Enemy” (1931). There were only some background gunshots that he used as a sound effect. It was a bold move from him, as the climax is one of the most critical things in a gangster movie. But, we are talking about some of the pioneering directors of American films; they dared to do whatever they wanted with this art form.

How Did Three-Strip Technicolor Add Benefits For The Illusionists?

In the 30s, the three-strip Technicolor was a gift for the directors to experiment more with a coloring palette in filmmaking. Blue could not be reproduced in the old two-strip Technicolor, but the three-strip technology brought in an entire spectrum of colors. Extra-wide cameras were now able to expose three negatives at the same time, each recording one of the primary colors. In John Stahl’s “Leave Her To Heaven” (1945), we see how three-strip Technicolor added a particular style to the melodrama rather than encouraging realism. The director always knew that color could play a dramatic role at times. In his “Johnny Guitar,” Nicholas Ray portrayed the vigilantes in black, while the outcasts were featured with rich colors, sometimes pure white. He deliberately distorted the colors and even toned down the Blue in favor of deep, saturated colors to establish the emotions.

The Era Of Cinemascope And How It Changed The Screen Size

With all the technical advancements, American filmmaking was slowly moving towards a new era of filmmaking, but the small cinema screens from the past couldn’t showcase the director’s growing vision, and hence the necessity for a wider cinema screen started to grow. In 1953, the first CinemaScope picture was released- “The Robe.” Initially, the aspect ratio change began to compete with the audience’s growing inclination toward television sets. In the latter stages, many filmmakers made the most out of the new aspect ratio. For example, Elia Kazan 1955 released his “East of Eden” and showed the world that CinemaScope could also intensify the family drama. He used narrower frames, such as corridors, within the wide format that CinemaScope produced. Masters like Vincente Minnelli in his 1958 release “Some Came Running” went even further with this new CinemaScope. He intensified the dramatic effect of scenes where the actors mixed into a crowd. The audience doesn’t know when the killer will come across his prey. Although Howard Hawk, at the beginning of his “Land of the Pharaohs,” said that the CinemaScope was only good for showing great masses and movement, it was tough to focus on details and edit. Later, his approach was victorious because of the masterful shot composition that inspired us to appreciate the human efforts of the pyramid builders.

The Introduction Of The Green Screen

Introduction of the Green Screen in filmmaking changed everything. Hollywood started making films with lavish sets and thousands of extras that it was becoming more and more costly to produce. Buying 3,000-4,000 extras for shots was not possible in modern times because of all the costumes, transportation, food, etc. With the introduction of the green screen, they achieved the same effect at a tenth of the cost. However, as the new age directors chose budgeted filmmaking over conventional methods, an argument started among the elites that these new directors had surrendered to technology instead of fighting for the art. But, Francis Coppola once clarified that this was never the case as cinema itself is a form of technology. From that point, some might argue that cinema should no longer be considered art. Coppola thought this argument was very naive because technology was never the source of creativity; instead, it has always been an element of creativity. We have to embrace technology as a medium to grow. This is what Stanley Kubrick did in his “2001: A Space Odyssey”. It was the first film to link the camera and the computer to create special effects for the spaceship’s journey. Every frame from this film speaks of the infinite possibilities for cinematic manipulation. This film became a revolution in itself that delivers your story through all the technical devices in your pocket.

Conclusion

So, was the grand tradition that started with “Cabiria” and “Intolerance” somehow lost, or did technology help American filmmaking to introduce a new era of films? It will always be a debatable point, but the very essence of cinema demands experimentation. What if D. W. Griffith hadn’t experimented with film reels and turned images into moving ones? Would we have “The Birth of a Nation” in such a case? Times are changing, and filmmakers have to adapt to the changing times. It’s not always necessary to implement all the technologies in a certain film, but what if that certain technology elevates your storytelling? The core and crux of filmmaking is to tell stories and to express emotions on screen. If the emotions are intact, it doesn’t matter much after a point what technology one uses to express them.

We have learned so far that the technologies helped the directors to be more creative with the art form. They introduced dialogues because they got Sound, used compositions and color palettes only after they had Three-strip Technicolor, and even made their screens larger than ever because of the CinemaScope. So, yes, technological advancement helped cinema grow in the best possible way. Next time, we will talk about the introduction of the green screen and how that revolutionized American filmmaking.