American filmmaking grew into something phenomenal technically and creatively before the 50s. They had technicolor, cinemascope, and almost everything required to shoot a film. When the 50s arrived, filmmakers started questioning the norms of society. The subtext becomes essential, just like the apparent subject matter. Films of that period generated the idea of the fragility of democratic institutions. The contexts of the stories started to become more socio-political; a piece of paper signed by a government official was considered more valuable than a man’s life. The storytelling changed; the smugglers (as discussed in the previous article) directly questioned the authorities.

How Did The American Filmmakers Make Subtext More Vibrant Than The Subject Matter?

The 1950s offered something more alarming than ever in terms of storytelling. Previously, we have said that “B” films always dared to impose any idea, but big-budget movies never had the freedom to do it. However, the 50s broke with this norm; big-scale pictures with major studio stars pointed out societal flaws, which impacted the audience. In his film “All That Heaven Allows” (1952), Douglas Sirk played the character of a widow who was accepted by her community. The widow fell in love with a much younger man, a professional gardener. This goes against society’s norms where a widow belonged to a circle of aristocrats. Soon, the widow was unhinged from her world; even in social gatherings, people offered an unusual glance at the couple. The unending turmoil between home and society took a toll on the widow when she decided to separate herself from her lover. This whole subtext presented a citation of American small-town life. Her children gave her a television, the ultimate symbol of alienation for the widow. Later, Douglas Sirk, in an interview, said that he always trusted his audience with their imagination. According to him, once a filmmaker starts teaching his audience, he makes a bad film.

Another director, Nicholas Ray, through his 1956 classic “Bigger Than Life,” introduced some unique devices by bringing the American family and the psychotic elements together. It was the conventions and the contradictions playing out in the same subtext. Nicholas Ray suggested that unless you see that a hero is as disoriented as yourself and makes the same mistakes as you, there will be no satisfaction when he does commit a heroic act. The great filmmaker once said that filmmakers must give the audience a heightened sense of experience. So, to do that, you must explore these little details in your characters. Among all the smugglers of the 1950s, Samuel Fuller was the most outspoken. According to Scorsese, no ideology escaped his fierce irony. He targeted American hypocrisy in most of his writings. One of the many reasons why it was hard to distinguish his heroes from his villains was through his “B” films; Fuller made it clear that the whole of America behaves like a mental hospital. Everyone has their own opinion about something, and some people march with them. His intention was evident in his 1963 masterpiece “Shock Corridor,” where the inmates of a mental hospital were the product of Cold War paranoia and Southern racism. Fuller masterfully represented every form of American insanity.

Runaway Production Was The Name Of The Game

By the end of 1960, the era of pioneers and showmen was gone, and replaced by agents and executives. Actors and directors started their own production companies; to make a film, the whole crew started traveling around the globe. Vincente Minnelli’s 1962 classic, “Two Weeks In Another Town,” was ironically a sequel to “The Bad And The Beautiful.” This film represented Hollywood’s decline from 1952 to 1962. In these ten years, the whole industry has gone through massive changes. The lead character of this film is a veteran director struggling with this change. He talked in an unsettling voice with his wife, abusing her with some hurtful words, yet cried in her arms, asking, “How can a man go wrong and not know why?” Is it ego? ” It was true that this rapid change in the industry shattered some of the veteran filmmakers, and this film talked about it.

The Age Of The Iconoclasts

Whereas the smugglers worked undercover, mainly in the “B” films, the iconoclasts directly attacked Hollywood’s conventions. Iconoclasts openly defied the system and expanded the art form. The system often defeated them, but sometimes they made the system work for them. Back in the silent period, Hollywood used to have a firm idea regarding entertainment. They always confused it with escapism; thus, borrowing the subject matter from real life was regarded as extremely dull, mainly if the subtext talked about the lower depths of society. But D.W. Griffith challenged the ideals of glamour and wholesomeness by introducing a series of realities into his films. According to Scorsese, D.W. Griffith is often identified with quaint romanticism and Victorian sensibility, but there were times when he went beyond the accepted melodrama of his time. In his “Broken Blossoms” (1919), he showed how corrupted reality could destroy the purest dreams. It was a tragedy of two lovers who were dominated by the norms of society. Their bodies suffer physical pain every moment while society’s structure bends their souls. Both of them were broken blossoms until they found each other. For a brief moment, they were alive, but soon when their reality collapsed with the existence of the town-people, the lovers couldn’t escape the fury of their racist father. The girl’s punishment was death, and the young Chinese, who hated violence, picked up a weapon to avenge her.

Conclusion

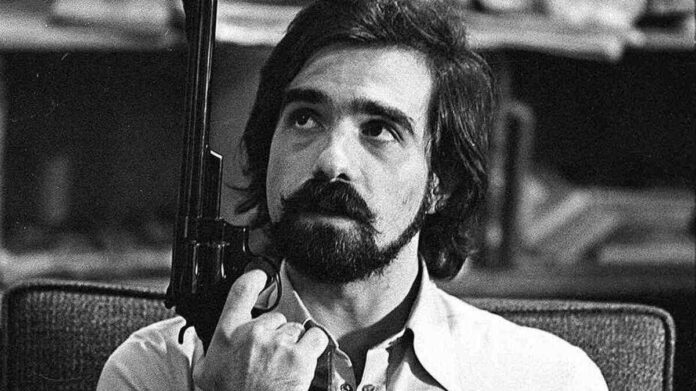

We have come to the edge of discussing the history of American filmmaking through the eyes of Martin Scorsese. We will talk about legendary directors in the last two pieces of this series. They constructed a new wave in the history of filmmaking—Orson Welles, Charlie Chaplin, Elia Kazan, Billy Wilder, Arthur Penn, and, of course, Stanley Kubrick. In the following article, we will discuss more of the iconoclasts and why Citizen Kane became a cult classic in the history of American filmmaking.