There are some people who remain etched in the collective memory forever—brought up constantly on the lives that they lived and the ideas that they passed on—kept alive through reading, even if it means being restricted to a single column in history books—kept alive in political movements when the resistance in contemporary times calls forth the mention of these glorious people. And the most powerful, kept alive through art. Many of us know Bhagat Singh through the numerous films made about him and his comrades. We know of them as those who went to the gallows at a very young age. And films made about people from history seldom contextualize their relevance in the modern day. That is where “Rang de Basanti” changed course in reminiscing the fearless youngsters who caused havoc to the colonizers with their ideas and acts, by telling a story of the disjointed and cynical youths of today who find resonance with them.

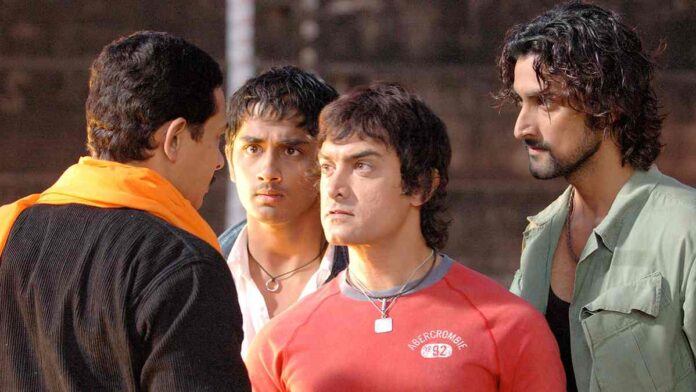

A documentary filmmaker from London comes to India to make a film on Bhagat Singh and the revolutionaries. There begins her quest to find an actor who would play the role. But seeing how misinformed and ignorant young people are about these revolutionaries puts her into despair. And finally, she manages to get people to act in the film and then begins a juxtaposed narrative with visuals from history merging with contemporary times. It is edited all seamlessly with relationships in the current times, finding echoes from the past time. It is not an overtly socio-political film, but the politics come out of its aesthetics. It is a story of friendship first and then turns into what decisions a group of friends make. And the film turns away from being just a passive engagement with these historical figures and is filled with ideas about bringing change and the awakening of a generation. It makes a statement about how the youth of the country need to wake up and give a purposeful turn to their lives.

The film also works as a pedagogical device. It tells us the lives of these revolutionaries in glimpses to make a larger point about what can be learned from their lives and whether situations are any different in the country today. The storytelling is also infused with radicalism, thanks to the masterful use of the camera by Binod Pradhan. The use of jarring slow motion to increase sentimentality is employed with a sepia tone to show the time of the revolutionaries. This sense of time and having close connections between past time and the present one is further used by Rakesh Omprakash Mehra in his later films as well, where it works smoothly in “Bhaag Milkha Bhaag” and meanders in “Mirzya.” It is a clever narrative device emerging out of “Rang de Basanti” which has thematic undertones that speak to the heart.

The storytelling brings out the complex themes and simplifies them. No longer do these figures seem to exist in a distant past, but their presence can be felt even today as we manage to make sense of the world around us. There are numerous examples of such blending. When Bhagat Singh pens a letter to his father telling him that he is going away from home and he doesn’t want to marry but wants to work to achieve freedom for his people and his country, Karan, at present, plays Bhagat Singh in the film that Sue is making. Acting as Bhagat Singh, with his emotional letter as a voiceover, he goes and bows to his parents. And then, Sue says, “Cut.” We are made to remember that they are making a film. Lights come on, and the color changes. We are back in current times with such swiftness. But the entire play has an effect on Karan. After the cut, he gets a call from his dad, with whom he shares a troubled bond. A connection is felt.

The film doesn’t feel threatening, considering how polarizing things get while speaking of socio-politics. Neither does it get overly sentimental while speaking of Bhagat Singh and the comrades. The music by AR Rahman evokes all kinds of feelings, especially in the song “Luka Chuppi,” another instance where a lot is spoken subliminally. Ajay’s mother is devastated by the loss of her son. It can be read off as a symbolic representation of the country. On a metaphoric level, with the mother crying for the death of her son, India as a motherland cries for how the conditions in the country have become. And then, the mother is injured during a protest against police violence, which again can be seen as a symbolic layer behind the literal. This is also when all of them get together and decide to do something about it. And they eventually do, again finding resonance with what the revolutionaries did all those years ago.

As they walk towards the radio in the climax, their shots are intercut with those of the respective people they played in the film. They became the revolutionaries of the present age. It is made widely apparent that instead of just worshipping these people from history, we can walk in their shoes to bring about change. The film, then, is about becoming and realizing. The characters, who have been living their roles in the story, now ask us to pass the baton. The last shot is a freeze frame where DJ and Karan look at us, smiling. Their eyes sparkled with satisfaction. And now, it is up to us who are watching to take away something and realize it. And that’s where “Rang De Basanti” emerges from the screen and engages us actively, leaving us with a question: Will we carry the baton forward?