Replete with stunning visuals, overarching themes, and a dash of surrealism, Iñárritu’s films are often a true spectacle of artistic audacity. As the name might already hint at, “Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths” has been his most ambitious venture so far. His latest film is a diptych that draws heavily from his personal struggles and goes on to probe into the very essence of ideologies. And then, it proceeds to portray that essence, even if it is only a paradox.

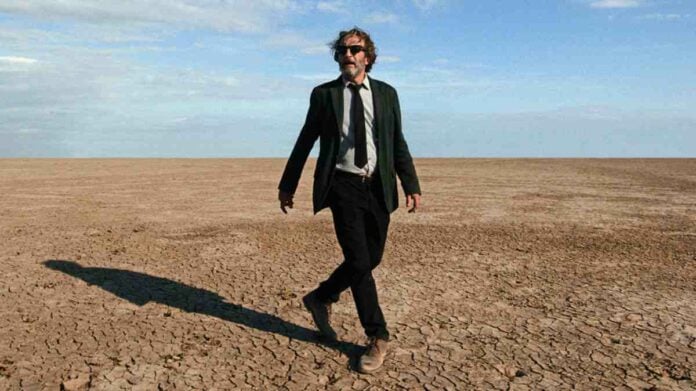

“Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths,” is a film that must be viewed in its entirety. In this dreamlike, semi-autobiographical account, somehow, every scene connects to every other scene, and every premise leads to an avenue of self-exploration. It makes one wonder how the filmmaker pulls off the feat of creating something that has so many dimensions embedded in every aspect of the film, each of which merits looking at minutely. A visual stream of consciousness guides Iñárritu’s film, where the character of a famous Mexican (but residentially American) journalist, Silverio Gama, takes center stage. As he visits his “homeland” before returning to the US to receive an award for his recent work of docufiction (which happens to share the same name as the film itself), he is found to be enmeshed in personal conflicts and questions of identity and existence.

The word “Bardo” in the title of the film has its roots in Tibetan Buddhism, which refers to a suspended state of existence suspended between death and rebirth. Later, this idea was expanded upon, and six different states of Bardo were defined, the Bardo of life, dreams, and meditation being a few of them. Essentially, it signifies a liminal state of being. There are no definite words that can do adequate justice to this ephemeral concept, let alone capture the crux of it. And yet, it is an all-pervading experience. This transient feeling is borne by the film through its intricately stacked layers of formless narrative. (Spoilers!) In a literal sense, Silverio is stuck in a state of Bardo, as is revealed at the end of the film, he is in a coma, lying in a hospital bed, and all his experiences are manifestations of his mind, which is subconsciously picking up cues from the conversations that are going on, and making connections with memory. But this is not the only duality in existence that the film hints at. One might say that Silverio exists in a state of Bardo, even in his personal life. He questions his fatherhood often. He is supposed to be with his family, but he is not. And he is unable to let go of the memories of his dead son, Mateo. Along the same lines, there is also the Bardo of his identity, as he struggles to understand what it means to belong to a country and finds himself stuck somewhere between both the nations and belonging to neither.

“Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths” succeeds in giving a fresh perspective to the overwrought ideas of nationalism, which seems to be the need of the hour. It manages to portray the conundrum of nationalistic sentiments and brings out the self-indulgence associated with it. When Silverio visits his homeland, which he no longer calls his home, there is a stark sense of alienation in him. It is evident that the love that he proclaims for Mexico is paradoxical by nature. This is, after all, a country that he chose not to live in. When he reinforces his appreciation for Mexican culture in front of his son, he retorts by saying that his father knows nothing about the people of his native land, turns a blind eye to their suffering, and questions his decision to raise his family in the States.

Silverio’s guilt is immensely aggravated by the fact that he is accepting an award from the United States, which he believes is a way of alleviating the hatred of Mexicans toward America. He is ashamed and feels that he will be a prime target of mockery in Mexico. This fear of humiliation caused him to shirk off a live interview with one of his former colleagues, Luis. Later, in a confrontation with Luis at a party, Silverio accuses him of being a petty dealer of opinions and a pretentious nationalist lacking artistic aptitude. And then, as if we were in Silverio’s head, Luis’s words were muted, though his lips were seen moving with vigor. When Silverio meets his extended family at another party, his cousins scoff at him for sucking up to the Americans, and he is seemingly indifferent to these slurs as well. But Silverio harbors within him a deep dissonance, which pokes its head out in a later sequence when security personnel at the US airport, a man of color, tells him that America is not Silverio’s or his family’s home. He loses his composure and demands an apology from the man.

One does not scorn Silverio for his life decisions. He is just a man who tries to ensure the best living conditions for his family. Nonetheless, the film provides ample scope to criticize his self-serving ideologies. But his conflicts stir up our thoughts. What does ethnic identity mean in a country that, as Silverio says at one point, is “a country of immigrants”? In one of the most surreal sequences, Silverio climbs up a giant pile of dead bodies to encounter Hernán Cortés, the Spanish conqueror who invaded the Aztec Empire and colonized the major parts of the Mexican mainland in 1519. While Silverio accuses Cortes of being a ruthless murderer, he proudly enunciates that, if not for him, there would be no Mexico.

In his collection of essays on nationalism, Rabindranath Tagore expounds a radical definition of “nation” as a group of people bound together by a mechanical purpose. The transactional nature of such organizations hinders the development of relationships between people, which is a natural form of self-expression for human beings. Instead, such a society gleans from a feeling of competitiveness and hunger for power and fails to account for the living reality. Iñárritu explores the idea of a nation as lodged in the mind of a man who discovers that the story of his nation is also the story of his becoming.

See more: ‘Bardo’ Ending, Explained: Did Silverio Take His Leap Of Faith? What Is This Fever Dream Of A Movie?